Table of Contents

Let’s cut through the fog of philosophical mumbo jumbo and get down to the brass tacks of hedonism, the ancient philosophy of chasing pleasure. Forget dense treatises and pompous lectures. Here’s your crash course in pleasure, ancient Greek-style, with a modern twist.

Where Hedonism Came From (Hint: Not a Frat House)

If the philosophy of hedonism were a reality TV show, Aristippus would be the guy flaunting his designer toga and guzzling imported wine, unapologetically declaring that life’s ultimate goal is an endless buffet of pleasure with zero room for pain. This 4th-century BCE Greek thinker, who kickstarted the Cyrenaic school of thought, had one big idea: life is about feeling good. Pain? That’s just bad vibes he’d rather not deal with. Aristippus wasn’t subtle—he called pleasure a “gentle and tender feeling” while painting pain as some kind of soul-wrenching, barbaric mosh pit.

Aristippus wasn’t just the founder of the Cyrenaic school; he was its poster boy, living large with a love for luxury and, let’s just say, a rather enthusiastic appreciation for courtesans. Aristippus preached that life’s goal is to bask in pleasure and dodge pain. He even poetically labeled pleasure as a “gentle and tender feeling” while calling pain a “harsh and turbulent movement of the soul,” which sounds like the kind of thing you'd hear in a spa commercial.

The Rockstars of Hedonism

Fast forward a bit, and along comes Epicurus, the philosophical buzzkill to Aristippus’s party vibes. Sure, Epicurus agreed that happiness is the ultimate goal, but he swapped out Aristippus’s "live for the moment" ethos for something a bit more, shall we say, refined. While Aristippus practically had “YOLO” tattooed on his toga, Epicurus said, “Hey, maybe let’s prioritize the soul over the body.” Translation? Skip the courtesans and fine wines; true joy comes from inner peace and not waking up with a hangover.

Epicurus took Aristippus’s hedonistic free-for-all and slapped it with a PowerPoint hierarchy, and put some serious thought into the whole “pleasure” thing. He didn’t just chase it; he categorized it. Think of him as the Marie Kondo of happiness—decluttering life down to a state he called ataraxia, or pure, unbothered bliss. Epicurus wasn’t about gorging on feasts or endless orgies, though (sorry to disappoint); he prioritized mental tranquility over physical thrills.

He categorized pleasures into three neat little boxes:

- Natural and Necessary: The basics—sleep, water, food. Stuff you can’t live without, unless you’re auditioning for a survivalist reality show.

- Natural but Not Necessary: Think fine dining and, uh, relationships with professionals of the night. These pleasures spice things up but won’t kill you if you pass.

- Unnatural and Excessive: The kind of overindulgence that turns your life into a bloated Greek tragedy—constant binge-eating, drunken debauchery, and that third helping of baklava when you know you’re already full.

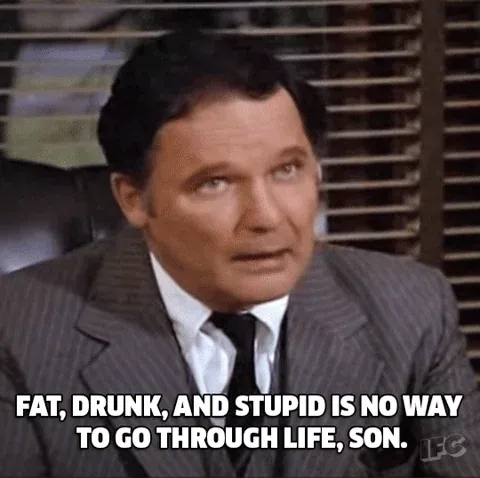

Epicurus might’ve turned the pleasure dial down a notch, but his point was clear: too much of a good thing is bad. Or, as he might’ve put it, if you’re stuffing your face at an all-you-can-eat buffet of life, don’t be surprised when you leave feeling nauseous instead of satisfied.

Then came the Enlightenment brainiacs—Hobbes, Helvétius, and Spinoza—who gave hedonism a face-lift. Their version said it’s totally cool to do things for enjoyment, just don’t ruin someone else’s day in the process. This pragmatic spin eventually birthed ideas like rational egoism and utilitarianism, which are basically a polite way of saying, “Do what you want, as long as everyone ends up vaguely happy—or at least not suing each other.”

The Gospel of Pleasure

Hedonism, in its broadest sense, is a philosophy that says, “Grab all the pleasure you can, and dodge the pain.” No guilt, no waiting for some mythical afterlife reward. Life is the reward, folks. This is where hedonism takes a swing at organized religion, arguing that you don’t need to spend your life in servitude waiting for the big payout. Live now, they say, and forget the moralistic nagging about “earning” your happiness.

Hedonism Today: Now With 100% More French Flair

Fast-forward to today, and hedonism is still kicking. French philosopher Michel Onfray has taken up the mantle, with over 100 books to his name, including The Invention of Pleasure: Fragments of Cyrenaics and The Possibility of Existence: A Hedonist Manifesto. Onfray’s spin? Be happy, make others happy, and for god’s sake, don’t hurt anyone. Also, keep tabs on yourself. If something feels off, adjust the plan and keep the pleasure train rolling. It’s like mindfulness, but with wine and cheese.

When Too Much Pleasure Fries the Circuit

Here’s where science kicks in and ruins the party. Pleasure, it turns out, is heavily reliant on dopamine, the brain’s party drug. Discovered in 1957, dopamine is the stuff that keeps you chasing the high. Too much, though, and your brain short-circuits. You can’t focus, can’t think straight, and before you know it, you’re spiraling into apathy and depression once the dopamine rollercoaster takes a nosedive. It’s the biological equivalent of eating an entire cake only to regret it when the sugar crash hits.

Light Bulb Moments

Congrats! In less time than it takes to doomscroll social media, you’ve just inhaled a six-minute masterclass on hedonism. It’s about joy, pleasure, and not overthinking things—because the biggest irony of hedonism is turning it into homework. So, take this knowledge, and go find your bliss—or at least a snack. And remember, as any good hedonist would say: Life’s too short for bad wine or boring philosophy.

Further Reading

A Hedonist Manifesto: The Power to Exist (Insurrections: Critical Studies in Religion, Politics, and Culture)

Michael Onfray passionately defends the potential of hedonism to resolve the dislocations and disconnections of our melancholy age. In a sweeping survey of history's engagement with and rejection of the body, he exposes the sterile conventions that prevent us from realizing a more immediate, ethical, and embodied life. He then lays the groundwork for both a radical and constructive politics of the body that adds to debates over morality, equality, sexual relations, and social engagement, demonstrating how philosophy, and not just modern scientism, can contribute to a humanistic ethics.